Why We Need More Indigenous Writers

Publishing needs more Indigenous publishers, but cannot rely on its Indigenous workforce alone to ensure it catches up with effective practices when it comes to Indigenous writers and writing, writes Sandra Phillips.

Eddie Koiki Mabo and others won in the High Court of Australia in 1992 that zero land—nobody’s land – was a fiction. We need more time to kill his lesser-known cousin, zero voice. Voice can mean a sound, a word or a voice; ideas that we – we being Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples – having no voice are part of an enduring colonial imaginary.

Bwgcolman midwife and nurse researcher Dr Lynore K Geia a referred us be ‘bound in a place of zero voice‘- the phraseology is significant. He says that as Indigenous peoples we have our voices, but the place of our contemporary existence – Australia – is not to hear or listen.

There have been some excellent recent public contributions to the maturation of Australian publishing. Bridget Caldwell-Bright Executives his plea for more Indigenous publishing professionals in conversations about diversity. She argues that Employment is “the only concrete way to ensure that Indigenous expression can exist without having to rely on the cross-cultural editorial relationship.”

Caldwell-Bright has a strength: less than 1% of Australian publishing professionals identify as First Nations in the Australian Publishing Industry Workforce Survey 2022 on diversity and inclusion. As a former editor of a publisher who trained and worked at Magabala Books and University of Queensland Press in the 1990s – and then succeeded Native Studies Press in the 2000s, I too was advocating for more career opportunities in publishing for us Mobs.

But the publishing industry cannot rely solely on its Indigenous workforce to ensure it catches up with effective practices for Indigenous writers and writings. The culture of the industry must change to effect sustainable, meaningful and continuous improvement.

Wuthathi/Meriam woman Terri Janke, an international authority on Indigenous cultural and intellectual property, is known for her innovative pathways between the non-Indigenous business sector and Indigenous peoples in business. She has developped protocols for the Australia Council, Screen Australia, City of Sydney and LendLease, among others.

His groundbreaking legal and scholarly work on Indigenous cultural and intellectual property rights, exemplified in his 2021 book real leads, can continue to be a beacon for industries, such as book publishing, that commercialize Indigenous cultures. Respecting these rights and sharing the benefits with indigenous creators are the touchstones of this still uncertain future.

Culture incubates literature. A larger national culture in competition with itself can never fully settle the terms of its preferred cultural expression. I often hear criticism based on what does or does not contain literary merit as a convenient alibi for what the critic does not feel comfortable with.

Enhancing our national literature with the Indigenous voice could be a mutually beneficial goal if we continue to mature our editorial workforce so as not to “clutter” our text – a request voiced by the late Ruby Langford Ginibi. ‘Gubberise’ is vernacular of the word ‘gubba’, which some believe is short for ‘government’ – which translates into the vernacular as white people.

I am Wakka Wakka and Gooreng Gooreng. I was brought up in the North Burnett region of rural Queensland, in the land of my ancestors, Wakka Wakka. I chose academia as my third career after policy research and then publishing. I have taught publishing and publishing studies, as well as literary studies.

In all the traditional study programs that I have organized as an academic, I have renovated teaching methods with essential indigenous knowledge, perspectives and resources. Nevertheless, communicating the many specific indigenous publishing issues to a mainstream (albeit mixed) audience is no simple task, primarily because there is no single style guide that can be adopted for all manuscripts. and all authors.

The push for a “how to” guide is understandable, but misguided. Australia is a continent of hundreds of First Nations. There are stark differences in language, history and culture here, and there are nuanced issues of voice, creativity and representation.

Editing any writing for publication is an act of cultural mediation. It takes heavy doses of diplomacy to get the best out of writers, combined with uncompromising pragmatism to get books to market on time. What constitutes the “best” in this journey is a value judgment – and value judgments derive from culture.

As you will learn in any editing apprenticeship or editing study course, there are three main types of editing. The first is structural editing – which arrangement best suits this story? The second is copy editing – is it well written, do the paragraphs and sentences collide, or do they pull the reader in and keep them on their reading journey? And finally, line editing: are the sentences scanned correctly, are typographical errors eliminated?

These are technical skills that can be taught. But favor cultural intelligence is a larger project.

Tips for Non-Indigenous Writers

Even if we achieved parity in the population of Indigenous professionals in the publishing industry, 96.8% of the industry would still not be us. Perhaps this explains why conversations about publishing Indigenous literature most often focus on how to improve the professionalism of non-Indigenous publishers.

In the same vein, I offer the following suggestions to non-Aboriginal publishers who are learning about Aboriginal cultures, vernaculars, authors and manuscripts.

- Make your first set of notes for yourself rather than on the manuscript, as your notes are likely questions arising from your status as a foreigner and your own knowledge gaps.

- Immerse yourself in Indigenous-led cultural environments – festivals, public lectures, theater and celebrations – to learn something of the larger cultural context that your formal learning may have left missing.

- Do background research on basic historical facts that your formal learning may also have overlooked.

- Read a lot, including diverse genres and works by Indigenous authors.

- Ask questions of the author, but avoid interrogations. Contextualize your questions by referring to what you think you understand and what you don’t, do the work to decenter your dominant cultural position, and let the text work on you and you.

- Acknowledge your role as a ‘first reader’, but avoid centering yourself as a proxy for a mainstream readership that you believe will not understand the Indigenous voice. What is the point of publishing Indigenous authors, if not for our unique Indigenous voices?

How Indigenous Publishers Can Improve a Book

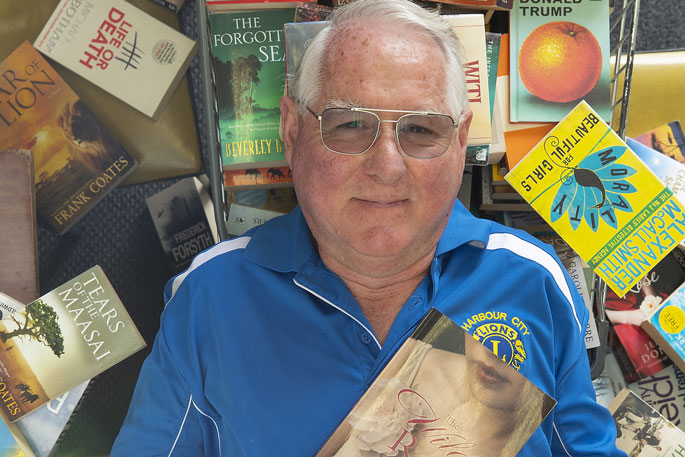

What about the rarer case of a native publisher and a non-native author? When I first sat down as an intern editor at Magabala Books, that was me.

I was reading a manuscript that should have worked for me: a collaborative synthesis of oral and archival history between an Aboriginal keeper and a white historian. It was a dramatic retelling of a story of Indigenous resistance and its key fighter. Jandamarra and the Bunuba resistance had all the things I loved to read.

But something was wrong. Instead of launching into the text with the proofreading symbols I was eagerly learning, I sat down with this manuscript and started to identify where I was uncomfortable: quoting pages and sentences and develop corresponding questions. Many questions, paragraph by paragraph, chapter by chapter. I had so many questions that I produced a separate report. From my perspective, the manuscript reads as an apologist for the views of the settlers.

My perseverance was rewarded with a stunning rewrite by the author – and the book went on to win the Historical and Critical Studies award at the 1996 WA Premier’s Literary Awards. While the Magabala Books website now lists the book as “out of print”, my doctoral research revealed that 15 years after first publication, the book was still being printed and sold by tour operators as a way for travelers to better understand the Kimberley region. I was, at the time of the first publication, quite delighted with the recognition by the author of my publicized interventions:

When the manuscript appeared ready for print, a new editor gave it a rigorous final review. Sandra Phillips seemed to know exactly the questions to ask. As a result, the manuscript has been refined to the point that I am happy with its release.

According to journalist and author George Megalogenis, Australia made history as the first English-speaking nation to become a predominantly migrant nation. He sees an urgent need for a “unifying story for the 21st century”, which could be found in the indigenous “roots of our family tree”. Although some Aboriginal people may argue that all non-Aboriginal people are migrants, it is worth considering.

What is our “unifying story”? We are a long way from a national literature brimming with stories of Indigenous writers, storytellers, creators and communities. Such an overflowing national literature may not produce a unifying history, but it could reveal a modern nation-state much more comfortable with the indigenous voice – an eradication of zero voice to support the eradication of zero earth.

Sandra Phillips is Associate Dean (Indigenous Engagement) in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Queensland. This is an edited excerpt from an essay first published by the Conversation. Read the full article here.

Category: Features