We asked the book-banning Republicans in Texas to define “pornography.” Here is what they told us.

While much of the national Republican discourse pushing for the banning of books from school libraries has focused on critical race theory and racial education, Texas GOP politicians have recently focused on just one slippery word to describe literature in the classrooms that they find offensive – “pornography”.

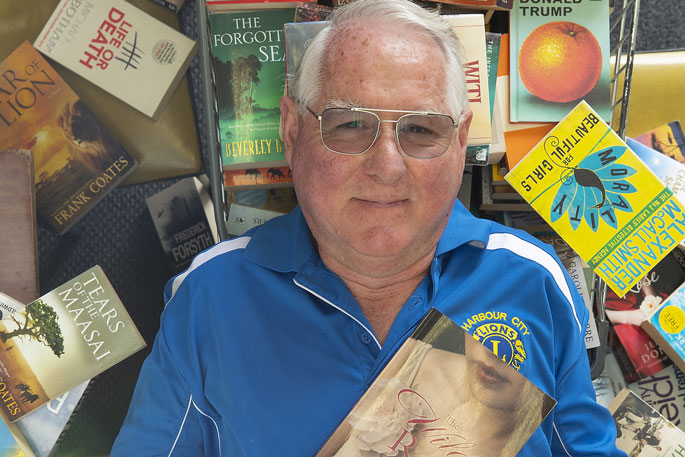

The word featured prominently in a March 2 letter written by Republican state Rep. Jared Patterson that was sent to school districts in Texas. Signed by 26 fellow Republican state lawmakers, Patterson’s missive suggested pledging not to buy books from sellers who supply “pornography” and specifically pointed to the graphic novel “Gender Queer: A Memoir” by author Maia Kobabe as an offensive example.

“Local districts and the Legislative Assembly will work diligently on policies to prevent such books from being allowed on campus in the future,” Patterson wrote. “However, we also recognize that school districts have a lot [of] market power when buying books and that if we unite against explicit materials for children, book sellers will be forced to adapt.”

The book in question has recently become one of the most challenged works by conservatives in the United States. Its narrative depicts Kobabe’s journey with gender identity and sexual orientation and occasionally features graphic illustrations of LGBTQ sexual experiences. In November, Gov. Greg Abbott cited “Gender Queer” in a call for an inquiry into whether students should have access to what he described as “pornographic books” in Texas schools.

So why are some books dealing with LGBTQ issues labeled as pornographic? We asked Abbott, Patterson and several other GOP members who signed his letter to offer their definition of the term. Of the 28 lawmakers we attempted to contact, only four responded, including Patterson, the author of the letter. Of those who responded, none offered a clear definition of pornography, with some pointing to existing Texas “obscenity” laws. Here is what they said:

Representative Jared Patterson: “The work I have done over the past few months, which includes the letter recently sent to the Superintendents of Texas, relates to the ban on making explicit and obscene material available to school children in public school libraries. The book ‘Gender Queer’ is a good example of explicit and obscene material, as it graphically depicts two young boys engaging in oral sex.This book, or something similar, is utterly inappropriate and should be removed from library shelves immediately public schools.

Representative Dustin Burrows: “The standard is set by the Supreme Court and the book ‘Gender Queer’ clearly meets that definition.”

Representative Matt Shaheen: “Section 43.21 of the Texas Penal Code defines obscene material as “obviously offensive representations or descriptions of ultimate sexual acts, normal or perverted, real or simulated, including intercourse, sodomy and sexual bestiality” . Specific examples found in public schools that fit the above definition include graphic images of women being raped by demons and small boys engaging in sexual acts on each other. Anyone who thinks this is acceptable is mentally ill. We will sue the vendors who sold this trash can to children in Texas.”

Representative Jeff Leach: “You know it when you see it. And if you see it and know it, these images must be quickly removed from all public school classrooms in Texas. »

Leach’s response is a reference to a quote from Justice Potter Stewart in Jacobellis v. Ohio Supreme Court of 1964, in which he could not describe the obscenity, but explained “I know it when I see it”. Shaheen says the example he cited was from Kumo Kagyu’s “Goblin Slayer” dark fantasy series, but he didn’t say which Texas schools had the title in their book collection.

Abbott’s office responded by directing us to their November letter in which it refers to the Texas Penal Code. However, the section it points to never mentions the word pornography. The term has been difficult to define, even for the highest court in the country.

Dr. Bryant Paul, a professor at Indiana University’s Media School who focuses on discourse around sex and sexuality, says the legal definition of pornography has been difficult for courts to pin down over the years. last centuries. While pornography enjoys First Amendment protection, obscenity does not, he explains.

“Since the invention of the printing press, [pornography] It used to be basically anything the church didn’t like that was considered obscene, so people had to be protected from it,” Paul says. “They weren’t as concerned about sexual content as they were about any content that made the church look bad.”

The world’s first law criminalizing pornography was the Obscene Publications Act of 1857, which was passed in the UK on similar grounds and rhetoric supported by Texas GOP members. “The legislature basically said that anything that could harm children, or that children shouldn’t be exposed to, should be banned,” Paul explains.

This idea was developed in Regina v. Hicklin (1868), a British court case in which a judge offered a broad definition of obscenity by asking “whether the tendency of the matter charged with obscenity is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences.” This legal test of obscenity became known as the Hicklin test.

The standard was eventually superseded in Miller v. California (1973), which described three tests for obscenity still used today. The first is “whether the average person applying contemporary community standards would find the work, taken as a whole, to appeal to lustful interest.”

“So it wasn’t if you or I found it offensive,” Paul explains. “It’s about whether people in the community think it’s offensive. There’s no national standard. It’s a local issue.”

The second part of the test asks “whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive manner, sexual conduct specifically defined by applicable state law.” The last question “whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value”.

“It’s still the standard for what counts as obscenity, but not necessarily pornography,” Paul explains. In Ginsberg v. New York (1968), courts proposed the concept of “variable obscenity” – material that might be considered obscene when viewed by children, but not when viewed by adults. This is the problem facing Republicans in Texas, Paul explains, not pornography.

Moreover, this movement on the part of conservatives indicates a return to the Hicklin norm. “They say any type of content that could harm a child should be removed from school libraries,” Paul says. “What makes it even sadder is that they openly say anything that’s not heteronormative will be harmful to children.”

Paul argues that such attacks violate the First Amendment and would likely not withstand scrutiny in federal courts. “Courts have ruled that virtually anything is protected unless it is deemed to be of no serious literary, social, political or scientific value,” Paul said.

Banning content on the periphery of what is acceptable sets a chilling precedent, Paul says. “When the people who support the ban start to cut corners on people’s right to consume certain types of information, you’re just seconds away in story time from hitting something those same people support,” he said. “That’s what should scare these people to death.”