Review: Silent star Buster Keaton rolls again in 2 new books

Two new books about silent film star Buster Keaton appear a century after they started filling theaters

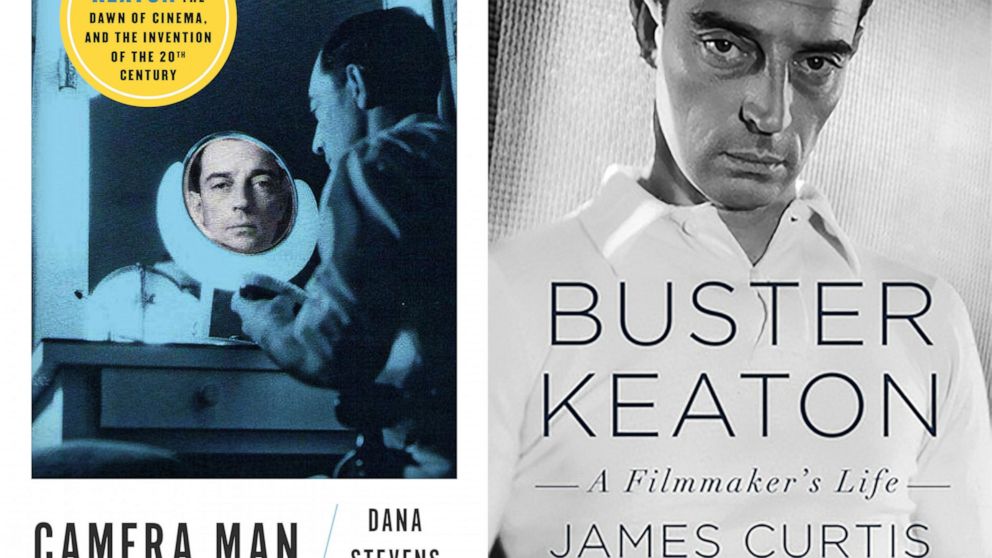

“Camera Man: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema and the Invention of the 20th Century” by Dana Stevens (Atria; on sale now); and “Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life” by James Curtis (Knopf; February 15):

You may not know his name, but you probably carry an image of Buster Keaton in your head.

He’s the guy who is chased through the streets by hundreds of policemen in the movie “Cops” (1922). He is the amorous train engineer sitting on a rising and falling locomotive rod as the engine pulls away in “The General” (1926). And that’s Keaton standing in front of a house as its facade crumbles in “Steamboat Bill Jr.” (1928), an open window saves him from being crushed.

The 1920s were the years when Keaton became an international star. The glow that accompanies a centenarian revives interest in his dark and funny outlook on life – a far cry from Charlie Chaplin’s sentimentality – and seems perfectly suited to today’s pessimism.

Two new books offer the choice of a dip or dive into Keaton’s world. The first is “Camera Man” by Dana Stevens, a film critic for Slate who reconsiders Keaton in the context of the tumult of the new century in which he thrived before withering away under the pressure of bad business decisions, bad marriages and many too much alcohol.

Closely following is veteran film biographer James Curtis’ ‘Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life’, a cradle-to-grave account of a career that has perhaps had more ups and downs than that of any other major film star. movie theater.

Keaton (1895-1966) learned the acting trade growing up on the vaudeville circuit, first as a cute addition to his parents’ act and later as a star attraction. A highlight involved Joe Keaton throwing his son onto the stage, a precursor to the incredible stunts adult Keaton would perform on film.

Keaton and the films matured over the same years. By 1917, moving pictures were no longer a novelty when considering his future, but rather the natural replacement for vaudeville as popular entertainment. Weeks after breaking up with the family act, he was pitching gags for comedian Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle’s movie studio and learning the new medium. Within a few years, Keaton was making movies under his own name, then ending the decade rivaling Chaplin and Harold Lloyd as Hollywood’s most reliable and inventive comedian.

In “Camera Man”, Stevens employs insight and colorful detail to connect critical turning points in Keaton’s life to the social and economic changes taking place in the United States. For example, she notes how the Keaton family opposed the Gerry Society, the groundbreaking child welfare agency. She details how mail-order kit houses inspired Keaton’s short comedy “One Week” (1920), in which a gift for newlyweds turns into a nightmare. Stevens also notes that the rise of Alcoholics Anonymous did not, alas, inspire Keaton to lay out of the bottle.

Sometimes, however, Stevens goes too far to make a point, such as exploring the history of the Childs restaurant chain because Keaton had breakfast there while contemplating his future. But such tangents can be a welcome diversion if you’re not interested in the full Keaton story.

Those who are will delight in Curtis’ overloaded book, which belongs in any movie fan’s library for taking a close look at the silent era and all of Keaton’s endeavors, whether big or small, triumph or failure. . There were more of these after Keaton was contracted to MGM, a factory that treated him like just another component of a movie-spitting machine, not a genius that needed space to create.

The arrival of sound was a stumbling block for a comedian who didn’t say funny things. The 1930s turned into a decade of popular and personal decline for Keaton. He ended up working at MGM for $100 a week creating gags for Red Skelton movies and such. Curtis recounts the lean years without letting Keaton get away with his part in damaging his own reputation.

The story allows Stevens and Curtis to end their books on higher, hopeful notes. Keaton’s salvation was the next big thing in entertainment: television. He appeared on early live shows, including a few of his own, and found work in offbeat roles on “The Twilight Zone,” “Route 66,” and other series well into the 1960s. he lived long enough to be rediscovered and to enjoy enthusiastic applause at special screenings of his old films.

Today, Keaton’s best movies are available online, giving him a presence in another big new release. Regardless of the medium, his comedy is like Vincent van Gogh’s brushstroke: better to see it than just hear about it.

———

Douglass K. Daniel is the author of “Anne Bancroft: A Life” (University Press of Kentucky).

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/gray/LMS4GGRVH5AB5IAHCD22D6S3SA.jpg)