Overview of book reviews: why art books, and… why now? ! ?

By Timothee Francis Barry

Can anyone tell me, please tell me, why there is suddenly such a profusion, a torrent… almost a glut, of important art history books hitting the market in this moment ?

Is this a byproduct of the stay-at-home, let’s-read-books-because-we-have-done-enough-with-Netflix thing?

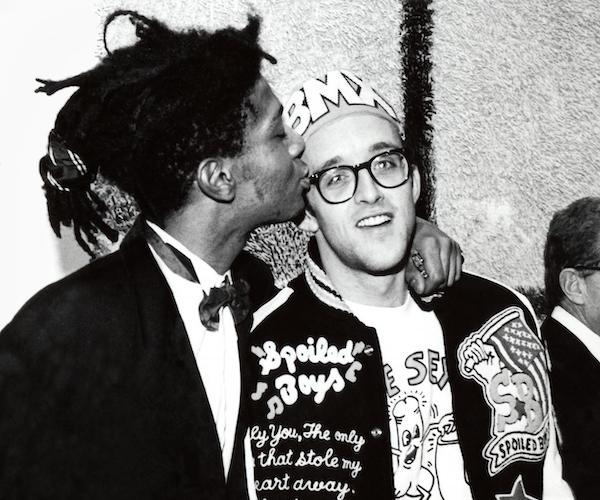

To know: the complete study of the eminent art historian Debra Bricker Balken Harold Rosenberg: The Life of a Critic (University of Chicago Press, 2021) and Myself and My Goals: Writings on Art and Art Criticism, by Kurt Schwitters, ed. Megan R. Luke (University of Chicago Press, 2021). There’s the coffee table-sized luscious tome Keith Haring | Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing the Lines (Princeton University Press, 2022), which was a slight disappointment – more on that. An outlier, George Rickey: A Life in Balance (Godine, 2021), turned out to be the choice of the litter.

So, art books. What are they for? In this day of myriad entertainment choices – stream this and download that, the whole yadda yadda podcast… could it be that we fancy going back to the simple pleasure of flipping through a nice picture book? Read an essay or two if it catches our attention?

Keith Haring | Jean-Michel Basquiat almost has an embarrassment of written riches. Artist Jenny Holzer provides an appreciation. Other contributors include George Condo, former Boston-based art-punk rocker with 80s band The Girls, now a top New York painter; Diego Cortez, Curator of ’80s Downtown New York; and Linda Yablonsky – bohemian New York doodler, eyewitness to stage misbehavior.

Yet somehow the parts of the volume do not constitute a winning whole, at least for this reader. The illustrations are top-notch but the essays are… okay (preaching already converted to welcome ease). No unreleased René Ricard pieces here, just the often reprinted 1981 art forum article in which Ricard (born Albert Ricard 1946-2014, New Bedford, Mass.) brought Basquiat to the attention of art world financiers. But yeah, it’s good to see it here. (Self-taught poet-critic Ricard also wrote career pieces about others, including painters Julian Schnabel and Brice Marden.)

Scenester Yablonsky’s oral history of the Club 57 stage is a detailed account of what performers wore, what they said, and what they drew on the walls. And, of course, it’s terribly fun to hear about Jean-Michel and Keith (who knew they were best friends?). At one point, Jean-Michel is delighted to sell five drawings to (legendary curator) Jeffrey Deitch for $50 each. Deitch still has them.

Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948) is a well-known name in the field of early 20th century collage, although admittedly his contributions to Dada art and its development are somewhat overshadowed by Marcel Duchamp, Tristan Tzara, Man Ray, and Francis Picabia. This anthology of his fascinating writings goes a long way to encouraging a re-examination of the German artist’s contributions to the forays and profound changes in artistic creation.

Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948) is a well-known name in the field of early 20th century collage, although admittedly his contributions to Dada art and its development are somewhat overshadowed by Marcel Duchamp, Tristan Tzara, Man Ray, and Francis Picabia. This anthology of his fascinating writings goes a long way to encouraging a re-examination of the German artist’s contributions to the forays and profound changes in artistic creation.

A really interesting aspect of this well-researched book is editor Luke’s highlighting of Schwitters’ Dadaist aesthetic: “a Dadaist is someone who takes the stage (the seats, including the dressing room and the tax of luxury cost 10 mark 65) and places a chamber pot on his head and toilet paper in his buttonhole, stammering man-bottle-drawer-table-stupid-dada-dada, and therefore he is a Dadaist-intellectual impostor….

Balken’s Harold Rosenberg, a biography of 656 pages, is in places a little painful. Rosenberg, (1906-1978) was big business in the art world (as the great journalists say) – in the 60s, that is. He and his slanderous rivalry with his nemesis, critic Clement Greenberg, have been the subject of much (some might think too much) chronicles. This point brings to the fore an uncomfortable yet elementary question: what is the value of criticism to culture?

I’ll leave that for others to ponder. Suffice it to say, this is a thorough work of scholarship – albeit a bit turgid in writing. Few who have written about Rosenberg can claim to have gone deeper into the weeds than Balken. Is this a must read? Art history professionals will raise their glasses; for the rest of us, only a maybe.

In contrast, George Rickey: A Life in Balance has everything a biography should have: up-close and personal first-person accounts of an artist’s daily life. Of course, you can very well ask “George who?” and that would be a valid question. Rickey (1907-2002) may be little known today, but in his time he was at the forefront of the world field of sculpture.

Rickey was an early pioneer of moving metal sculptures, often, but not limited to, large outdoor pieces. Aesthetically similar to his upstate neighbor, metal sculptor David Smith, he has sometimes been derided by critics as an Alexander Calder impersonator. Throughout his career, Rickey never stopped quietly innovating – he paid little attention to the naysayers.

Rickey was at the forefront of the Documenta 1966 world avant-garde art fair, a figure as famous as Andy Warhol. He had a studio in upstate New York that attracted curators like Alfred Barr, Jr. of the Museum of Modern Art, who presciently acquired a sculpture that adorned MOMA’s courtyard soon after. We follow his trajectory as a WPA muralist, decorating rural post offices in the Midwest to teaching and influencing a generation of artists. We see him at work and at exhibitions of his pieces in New York, California and Berlin.

Rickey was at the forefront of the Documenta 1966 world avant-garde art fair, a figure as famous as Andy Warhol. He had a studio in upstate New York that attracted curators like Alfred Barr, Jr. of the Museum of Modern Art, who presciently acquired a sculpture that adorned MOMA’s courtyard soon after. We follow his trajectory as a WPA muralist, decorating rural post offices in the Midwest to teaching and influencing a generation of artists. We see him at work and at exhibitions of his pieces in New York, California and Berlin.

But what makes this portrait so engaging and page-turning is this: its shadows behind shadows peek into the personal lives of the artist and his imperious, mercurial wife Edie as we follow their itinerant routes. Plus, the descriptions of his largesse to emerging artists and art-world figures make for intriguing reading. An interesting note: Rickey “helped support the brilliant young art historian Debra Balken [future Harold Rosenberg biographer] when she was fired as director of the Pittsfield Museum.

Rathbone, daughter of Perry T Rathbone, longtime director of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (from 1955 to 1972), made very good use of her status as an art world insider, using her connections to open avenues enlightening research. . She knows where the bodies are buried and does not hesitate to share the places with the reader.

Tim Francis Barry studied English Literature at Framingham State College and Art History at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth. He wrote for Magazine to go, New musical express, the Noise, Brooklyn Railroad, and the boston globe. He owns Tim’s Used Books and TB Projects, a contemporary art space, both in Provincetown.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/gray/LMS4GGRVH5AB5IAHCD22D6S3SA.jpg)