Obituary of Jack Higgins | Books

Under his own name and several others, including Jack Higgins, Harry Patterson had published 35 thrillers before, in his forties, hitting the jackpot with The Eagle Has Landed (1975), an instant bestseller in the United States, says it has sold over 50 million copies worldwide.

Its success drove Higgins, who died aged 92, into tax exile in Jersey, to a mansion overlooking St Aubin’s Bay, from where he was to write a popular thriller almost every year, his books guaranteed to find a place in every airport departure lounge in the world.

With commercial popularity came the opprobrium of literary critics: accusations of poor writing and recycling of characters and plots from earlier books. The New York Times said his bestseller Night of the Fox (1986) had “a plot that thickens to the point of freezing” and one reviewer described Thunder Point (1993) as “the best book on consumerism never before seen”, noting that references to drinking champagne outnumbered Scotch by 39 to 16.

Patterson, who claimed to have been advised by fellow author Alistair MacLean never to read reviews, rarely responded publicly to his detractors and was quite open about his “recycling” when it became clear that On Dangerous Ground (1994) was a reworking of his earlier thriller Midnight Never Comes (1966). He certainly didn’t shy away from reusing names, with characters going by the names of Hugh Kelso, Harry Kelso, Max Kelso and even (twice) Martin Fallon, who would then become one of his aliases, alongside Hugh Marlowe, James Graham and, from 1968, Jack Higgin.

The lack of “literary” recognition probably hurt, as did the mixed reviews for the dozen or so films made from his books (he was a big movie buff and from 1993 a patron of the Jersey Film Society), plus the fact that he was ever, in genre, shortlisted for a Crime Writers’ Association award.

Yet Patterson had an undeniable talent for spotting popular history and was particularly quick with Exocet (1983), in the aftermath of the Falklands War, and Eye of the Storm (1992), following a mortar attack on the office of John Major. Above all, he created a series of flawed heroes who were “good guys fighting for rotten causes”, including Steiner, the “good German” in The Eagle Has Landed, and Liam Devlin and Sean Dillon, who both had background of IRA gunmen.

This last trait caused some concern among his editors at William Collins, the editor he joined in 1971, as did his plot plan for The Eagle Has Landed. Patterson was told, “Nazis trying to kill Churchill? Where are your heroes? The book was first released in the United States and was an instant hit, confirming Patterson’s faith in the idea, and he later said, “It taught me one thing. Never, ever listen to editors.

The Eagle Has Landed established the Jack Higgins brand name worldwide, and Patterson rarely used his other writing identities thereafter. Within a year of its publication, the book was filmed by veteran action director John Sturges, with an all-star cast led by Michael Caine, Robert Duvall, Donald please and Donald Sutherland.

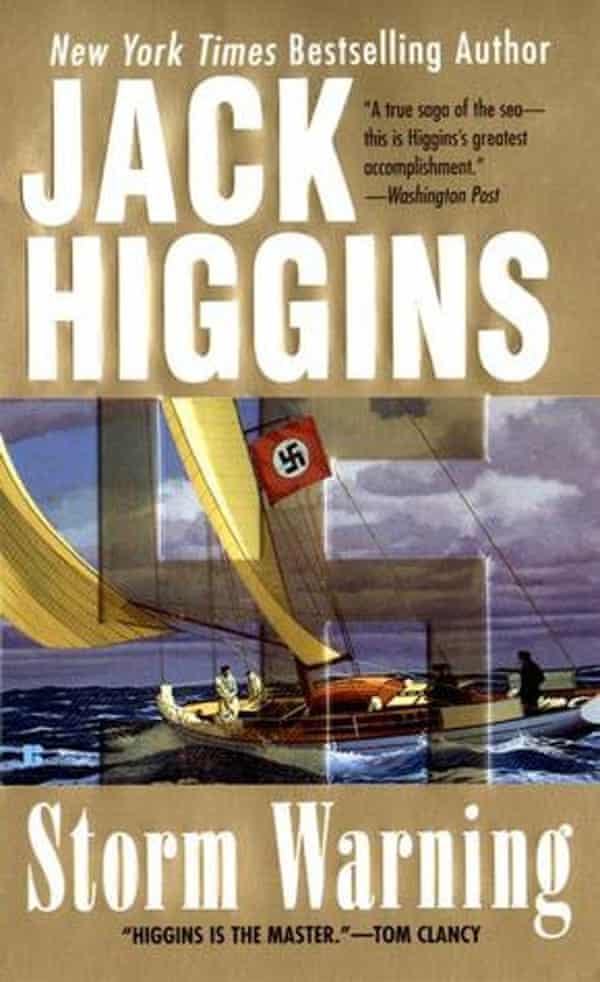

His next book, Storm Warning, also based on a World War II story, was a bestseller in 1976 and a film version was said to be three weeks from principal photography when it was released. cancelled. Patterson claimed he never found out why, but nonetheless “made a lot of money” from the project.

Faced with a super-tax regime in the UK, Patterson fled into exile in Jersey. He was still writing by hand and his writing regimen was said to start each evening at his favorite Italian restaurant in St Helier and then continue at home all night before a glass of champagne and a bacon and egg breakfast at dawn, then to bed. In 2003, the BBC reported its annual revenue at £2.8 million.

Patterson’s life story had a ring of rags to riches that wouldn’t have been out of place in his fiction. Son of Henry Patterson and Rita Higgins Bell, he was born in Newcastle upon Tyne, but when he was two his parents separated and his mother moved to Belfast, where young Harry was raised by his family enlarged. He attended Nettlefield Primary School (as did future footballer George Best some 20 years later) and claimed to have witnessed his first sectarian bombing at the age of six. He was forever grateful for Belfast Public Libraries and became an enthusiastic and fluent reader.

Barely a teenager, Patterson was transferred to wartime Leeds, where his mother remarried and worked as a waitress. He described himself as coming from a “poor background – a very working class”, but applied himself enough to win a scholarship to Roundhay High School, a classic escape route to advancement that he didn’t. failed to borrow. Beaten by the principal for throwing a snowball at the school clock, Patterson was told, “You’ll never be worth anything,” a judgment he will often remember with pride, especially when receiving an honorary doctorate from Leeds Metropolitan University in 1995.

He served in the Household Cavalry for his national service (1947-1950), reaching the rank of corporal and a posting as a guard on the East German border. He also, through army testing, discovered that he had an IQ of 147 and this realization prompted him to return to his studies once back in civilian life. Subsisting on a variety of jobs, including streetcar conductor and circus hand and eventually finding his way into teaching, he spent his free time writing short stories, plays and radio scripts that didn’t failed to attract publishers or payment.

In the 1950s he was accepted into the Beckett Park teacher training school in Leeds and also enrolled in a ‘distance learning’ degree course in sociology at the London School of Economics. He was one of two external candidates to take the final examinations at Bradford in 1961, during which he passed a third, making him one of the first graduates of the new discipline of sociology in Britain.

Although now married and starting a family, Patterson, the trained teacher, seemed to enjoy the bohemian life of late 1950s Leeds, befriending unknown young actor Peter O’Toole and the recently published novelist John Braine. It was while Patterson was lecturing at Leeds Polytechnic that literary agent Paul Scott finally found a publisher for his adventure thriller Sad Wind from the Sea, which is set in South China Seas he never knew. had ever seen, in 1959. Patterson was 29 and paid an “awesome” £75 in advance.

Thrillers, mystery novels and spy stories flowed effortlessly under a handful of pen names, though many had print runs just large enough to meet public library demand, but his fan base grew, albeit in the shadow of other thriller writers such as MacLean, Hammond Innes and Geoffrey Jenkins. “I had done well,” Patterson was to say, “but I hadn’t done brilliantly.”

The early ’70s saw more attention to the character in his writing, solid commercial success, and even rave reviews. His war story A Game for Heroes, published in 1970 by Macmillan as James Graham, is set in the Channel Islands, a place he would return to many times in fiction and, later, in life. It was fairly well received, but it was his next two books at Collins, as Jack Higgins, that were to make his name.

The Savage Day (1972) and A Prayer for the Dying (1973) centered on the Troubles in Northern Ireland and publication coincided with the release in 1972 of a film of an earlier book, The Wrath of God, with Robert Mitchum and Rita Hayworth. . Whatever Harry Patterson was thinking, Jack Higgins was starting to do it brilliantly.

Despite initial skepticism from his UK publisher, Patterson continued his research for The Eagle Has Landed, with the actual writing taking eight weeks. He is accused of threatening to take the book away when he discovered Collins was planning a first hardback print run of “only” 8,000 copies. First published in the United States, it became (according to the author) a “publishing legend” and when it finally appeared in Britain it was to remain in the top 10 lists for 36 weeks.

Twenty years later, in a preface to one of the many reprinted editions, Patterson wrote: “I can also say that it changed the face of the war novel.

If he were never to reach such heights again for a single book, Patterson had taken the quantum leap into thriller stardom and for the next 30 years the Jack Higgins brand guaranteed commercial success, with total sales estimated at more than 250 million copies. In an interview in 2014he said, “I didn’t see the point of writing books that didn’t make money.”

In addition to four young adult novels, co-authored with Justin Richards, Patterson wrote more than 70 novels, and on the cover of later books his publisher labeled him: “The Legend Jack Higgins.” His last published novel, the 22nd featuring Sean Dillon, was The Midnight Bell (2017). In 2021, a compendium edition of his trilogy of crime stories from the 60s was released under the title Graveyard to Hell.

Patterson is survived by his second wife, Denise Palmer, literary agent, whom he married in 1985; and by three daughters, Sarah, Ruth and Hannah, and one son, Sean, from his first marriage, to Amy Hewitt, which ended in divorce.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/gray/LMS4GGRVH5AB5IAHCD22D6S3SA.jpg)