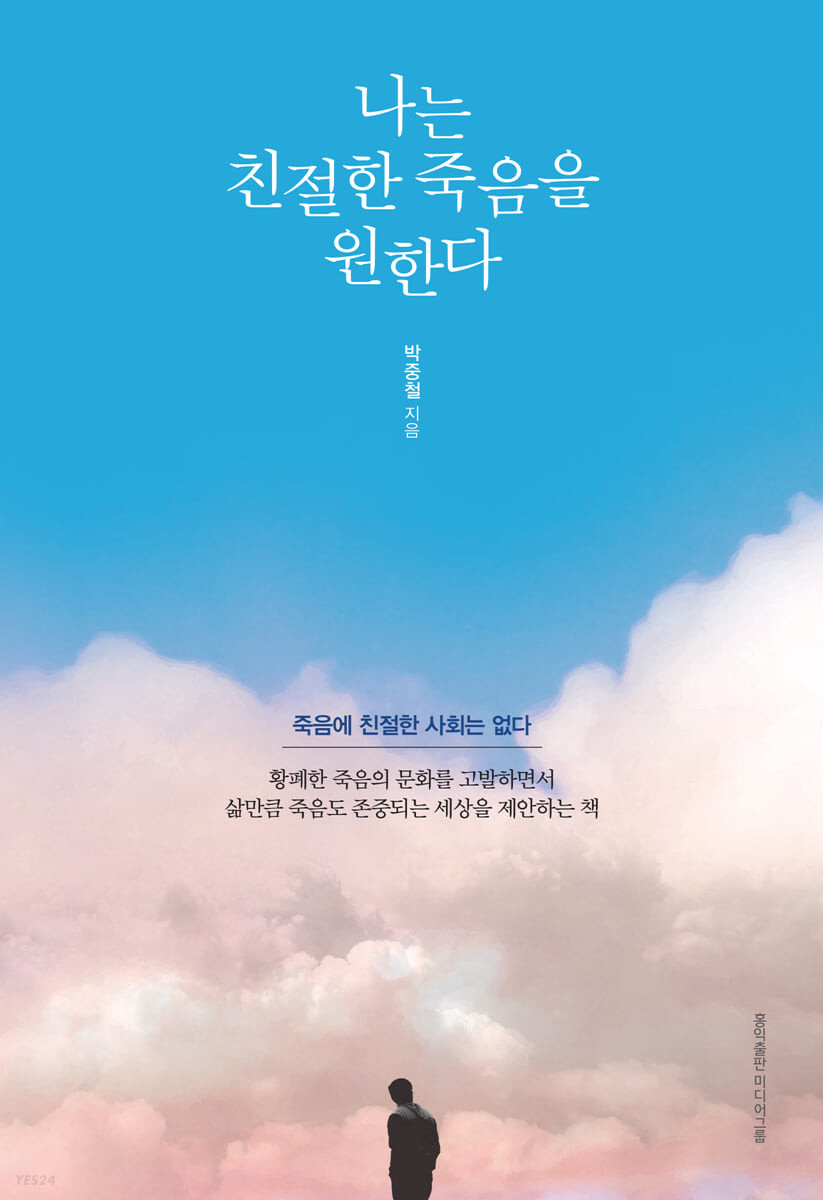

hospital bed sightings show what death means to Koreans

|

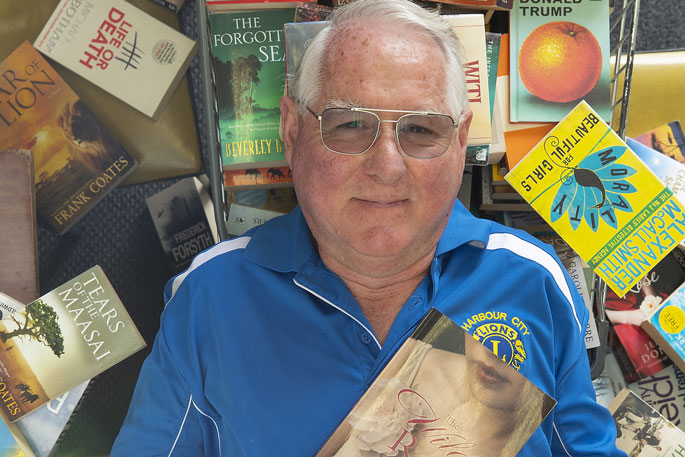

“What a Thousand Deaths Taught Me” by Kim Yeo-hwan, Forest Books |

Death may be the only thing that happens to everyone indiscriminately, but talking about it has long been considered taboo in South Korea.

“I wouldn’t dare talk about death with my parents, much less imagine their death,” would probably be the current thought in most Koreans’ minds.

Perhaps the sudden deaths caused by the protracted COVID-19 pandemic and an increasing amount of discussion about what is considered a “dignified death” allow us to consider the question. A number of books published recently are an indication of this phenomenon.

“This Is How You’ll Die,” “What A Thousand Deaths Taught Me,” and “I Want a Sweet Death,” all of which were released last year, deal with the concept of death. These books, all written by doctors, attempt to provide an alternative perspective on death and alleviate some of the fear that surrounds it.

Lessons from palliative care beds

The authors agree that South Koreans do not confront the idea of death enough or at least not in a direct and logical way.

“We live in a time where thinking about death equals life failure or actively thinking about death is associated with suicide,” says Kim Yeo-hwan, author of “What a Thousand Deaths Have Taught Me.” and former hospice doctor. “So we try not to look at the bare face of death, but it’s only after we lose someone close like our parents, our spouse or our child that we recognize the reality of death.”

Giving insight into the final days of dying patients and the lessons they leave behind in her collection of essays, Kim explained that people have little understanding of palliative care, which focuses on the palliative care of phased patients. who are close to death while also tending to their emotional and spiritual needs.

Even his son, then a medical student, once asked him why people should care about palliative care when they are not about to die, and that he wanted to be a talented doctor who saves lives. , not a palliative doctor who just watches over them. die. Her son’s comments were just one example of the many misunderstandings about palliative care and pain relief. People have a false narrative about hospice as a place you go to when you give up on life, and some consider using morphine to relieve the pain of seriously ill people like drug abuse.

|

|

“That’s How You’re Gonna Die” by Baek Seung-chul, Sam&Parkers |

Unnatural deaths

“This Is How You’re Gonna Die” and “I Want a Gentle Death” aim to change our perception of how we should die and remind us that the “automated death process” Koreans are used to is an end tragedy in a person’s life.

Even though Koreans have long considered dying painlessly at home surrounded by family to be the happiest death, people are forced to have an “automated death process” of being taken to hospital, receiving life-saving treatment and end their lives in an intensive care unit. . It has become standard practice since a particular incident in 1997, according to Park Joong-cheol, a doctor and author of “I Want a Kind Death”.

A group of doctors at a medical center discharged a critically ill patient at the request of the patient’s wife due to medical expenses. The doctors and wife were later charged with aiding and abetting the murder. The incident changed the way we die overnight.

Until the 1990s, the majority of people (75%) in South Korea died at home, with only 15% of the population dying in a hospital, according to 1991 statistics. Over the past 30 years, the numbers have changed. Today, only 14% of people die at home, while 76% are likely to die in medical facilities like hospitals or nursing homes. This figure is higher than the 54% in the UK as well as the US, where only 9% of people die in healthcare settings.

Unfortunately, home deaths are complicated by the need to obtain a death certificate from the hospital. “Because of this, there are no natural causes of death these days,” writes Baek Seung-chul of “This Is How You Will Die.”

The author, a dermatologist who regrets not having had enough conversations about death with his father, said a death certificate can only be obtained after the hospital confirms that the person is dead and that an investigation took place.

|

|

“I Want a Sweet Death” by Park Joong-cheol, Hongik Publishing Media Group |

Isolated death

In 1971, 94% of people were buried after death, a practice heavily influenced by Confucianism. Thanks to this practice, more than 1% of the national territory of South Korea has become burial grounds. While a living person occupied an average of 19.8 square meters of land, the average burial site was 50 square meters. In 2019, 88.4% of deceased South Koreans were cremated. Additionally, abandoned burial sites that have not been maintained by family members for more than 10 years now account for 20% of all burial sites.

While cremation is a growing global trend, Kim of “I Want a Kind Death” argues that fewer burial sites is an indication of death’s isolation. Death is isolated and treated in hospitals, funeral homes and crematoria, completely separate from life, he says.

However, “hospitals, to which almost all the social functions related to death seem to have been transferred, are indifferent to the protection of the peaceful deathbed of the patient and are rather obsessed with maintaining life against death until the end,” Kim said. As a result, the most miserable tragedy of advanced medicine — life-sustaining treatment, keeping someone neither alive nor dead — keeps us from having a human death, he notes.

Both Kim and Baek argue that patients should have more power to decide how they die.

Fortunately, in 2016, the Life Sustaining Treatment Decisions for End-of-Life Patients Act was passed and came into force in 2018. It allows a patient to opt out of four types of medical assistance such as CPR, a respirator, hemodialysis and cancer drugs. By the end of August this year, more than 1.42 million people had enrolled in a life-saving treatment plan.

However, there are many gaps and ambiguities in the law. For example, nutritional support cannot be stopped, contributing to undesirable life extension.

These books tell us that death is not something to be avoided. In fact, it’s an impossible goal, because it eventually happens for all of us. On the contrary, death should be contemplated deeply and discussed with loved ones, because death is part of all our lives – as important as life itself. And as the author of “What a Thousand Deaths Have Taught Me” says, “If you invest your time and your heart in death, death won’t change, but your life will.”

By Park Ga-young (gypark@heraldcorp.com)