Hitting the Books: How Mildred Dresselhaus’ Research Proved We Got Graphite All Wrong

Mildred Dresselhaus’ life was a life against all odds. Growing up poor in the Bronx — and even more to her detriment, having grown up as a woman in the 1940s — Dresselhaus’ traditional career options were paltry. Instead, she became one of the world’s foremost carbon science experts as well as the first female institute professor at MIT, where she spent 57 years of her career. She collaborated with physics luminaries like Enrico Fermi and laid essential foundations for future Nobel Prize-winning research, headed the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, and was herself awarded the National Medal of Science. .

In the excerpt below from Carbon Queen: The Remarkable Life of Nanoscience Pioneer Mildred Dresselhaus, author and deputy editorial director at MIT NewsMaia Weinstock, recounts the time when Dresselhaus collaborated with Iranian-American physicist Ali Javan to study exactly how charge carriers – aka electrons – move through a graphite matrix, a research that would shake completely understand the domain of how these subatomic particles work.

MIT Press

Extract of Carbon Queen: The Remarkable Life of Nanoscience Pioneer Mildred Dresselhaus by Maia Weinstock. Reprinted with permission from The MIT Press. Copyright 2022.

A CRITICAL TOUR-DE-FACE

For anyone with such a long and accomplished research career as that of Mildred S. Dresselhaus, there are bound to be some papers that might get a little lost in the corridors of the mind – papers that only make moderate progress. , perhaps, or which involve relatively little effort or input (when, for example, being a minor consulting author on an article with many co-authors). Conversely, there are always notable papers that one can never forget – for their scholarly impact, for coinciding with particularly memorable periods of one’s career, or simply for being unique or bestial experiences.

Millie’s first major research publication after becoming a permanent MIT faculty member fell into the standout category. It was a story she repeatedly described in her Career Memoirs, noting it as “an interesting story for the history of science”.

The story begins with a collaboration between Millie and Iranian-American physicist Ali Javan. Born in Iran to Azerbaijani parents, Javan was a talented scientist and award-winning engineer who became well known for his invention of the gas laser. His helium-neon laser, invented with William Bennett Jr. while they were both at Bell Labs, was a breakthrough that made possible many of the most important technologies of the late 20th century, CD players and from DVD to barcode reading systems and modern fiber optics. .

After publishing a few papers describing her early magneto-optical research into the electronic structure of graphite, Millie was looking to dig even deeper, and Javan wanted to help. The two met during Millie’s work at Lincoln Lab; she was a huge fan, once calling him “a genius” and “an extremely creative and brilliant scientist”.

For her new work, Millie aimed to study the magnetic energy levels in the valence and conduction bands of graphite. To do this, she, Javan and a graduate student, Paul Schroeder, used a neon gas laser, which would provide a sharp point of light to probe their graphite samples. The laser had to be built specifically for the experiment, and it took years for the fruits of their labor to ripen; indeed, Millie moved from Lincoln to MIT in the midst of work.

Had the experiment yielded only mundane results, consistent with anything the team had ever experienced, it would still have been a groundbreaking exercise as it was one of the first where scientists used a laser to study the behavior of electrons in a magnetic field. But the results were by no means trivial. Three years after Millie and his collaborators began their experiment, they discovered that their data told them something that seemed impossible: the energy level spacing in the valence and conduction bands of graphite was totally different from what what they expected. As Millie explained to an elated audience at MIT two decades later, this meant that “the group structure that everyone had been using up to then certainly couldn’t be the right one and had to be turned upside down.”

In other words, Millie and her colleagues were about to overturn a well-established scientific rule – one of the most exciting and important types of scientific discoveries one can make. Much like the landmark 1957 publication led by Chien-Shiung Wu, which overturned a long-accepted particle physics concept known as parity conservation, overturning established science requires a high degree of precision and confidence in his results. Millie and her team had both.

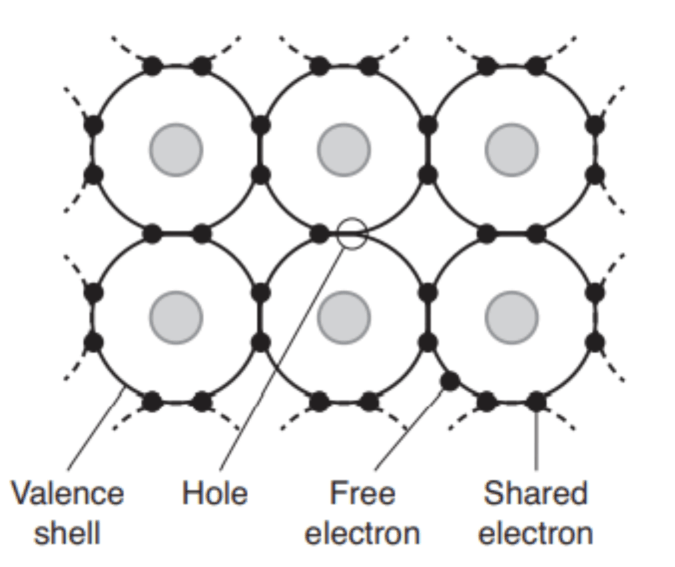

What their data suggested was that the previously accepted placement of entities known as charge carriers in the electronic structure of graphite was in fact retrograde. Charge carriers, which allow energy to flow through a conductive material such as graphite, are essentially what their name suggests: something that can carry an electrical charge. They are also critical for the operation of electronic devices powered by a flow of energy.

Electrons are a well-known charge carrier; these subatomic bits carry a negative charge as they move. Another type of charge carrier can be observed when an electron moves from one atom to another in a crystal lattice, creating a sort of empty space which also carries a charge, a charge equal to the electron but of opposite charge. In what is essentially a lack of electrons, these positive charge carriers are called holes.

MIT Press

FIGURE 6.1 In this simplified diagram, electrons (black dots) surround atomic nuclei in a crystal lattice. Under certain circumstances, electrons can break free from the lattice, leaving an empty place or hole with a positive charge. Electrons and holes can move around, affecting the electrical conduction in the material.

Millie, Javan and Schroeder found that scientists were using the misallocation of holes and electrons in the previously accepted structure of graphite: they found electrons where the holes should be and vice versa. “It was pretty crazy,” Millie said in an oral history interview in 2001. “We found that everything that had been done on the electronic structure of graphite up to that point was reversed.”

As with many other discoveries that subvert conventional wisdom, acceptance of the revelation was not immediate. First, the journal to which Millie and her collaborators submitted their article initially refused to publish it. In telling the story, Millie often noted that one of the referees, her friend and colleague Joel McClure, came out privately as a critic in the hope of convincing her that she was embarrassing off base. . “He said,” Millie recalled in a 2001 interview, “‘Millie, you don’t want to post that. We know where the electrons and the holes are; how can you tell they are upside down?’ But like all good scientists, Millie and her colleagues had checked and double-checked their results many times and were confident in their accuracy. And so, Millie thanked McClure and told him they were convinced they were right. “We wanted to publish, and we…would risk ruining our careers,” Millie said in 1987.

Giving their colleagues the benefit of the doubt, McClure and the other reviewers approved the paper for publication despite findings that went against the established structure of graphite. Then a funny thing happened: Bolstered by seeing these conclusions in print, other researchers emerged with previously collected data that only made sense in light of an inverted assignment of electrons and holes. “There’s been a whole flood of publications supporting our discovery that couldn’t be explained before,” Millie said in 2001.

Today, those who study the electronic structure of graphite do so with the understanding of charge carrier placement gleaned from Millie, Ali Javan, and Paul Schroeder (who ended up with a rather remarkable thesis based on the group’s findings). For Millie, who published the work during her first year on the MIT faculty, the experience quickly cemented her position as the Institute’s Outstanding Researcher. While many of her most remarkable contributions to science were yet to come, this first discovery was one she would remain proud of for the rest of her life.

All products recommended by Engadget are selected by our editorial team, independent of our parent company. Some of our stories include affiliate links. If you purchase something through one of these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.