Essay: The Enduring Popularity of Used Books

Aviation magazines fascinated Aadil Desai (56) when he was a student. But since ordinary libraries and bookstores in Mumbai did not keep them, he turned to raddiwalas.

“I often received new copies for a fifth of the price because the publishers threw away the unsold ones,” recalls Desai, who believes that reading these magazines paved the way for his career as a maintenance engineer. aircraft.

Good business helped his former student and continues to help the bibliophile he has become. Desai’s collection, which includes biographies, ancient books, and volumes on art, astronomy, and history, numbers in the thousands. He now pays rent to a vendor to store it.

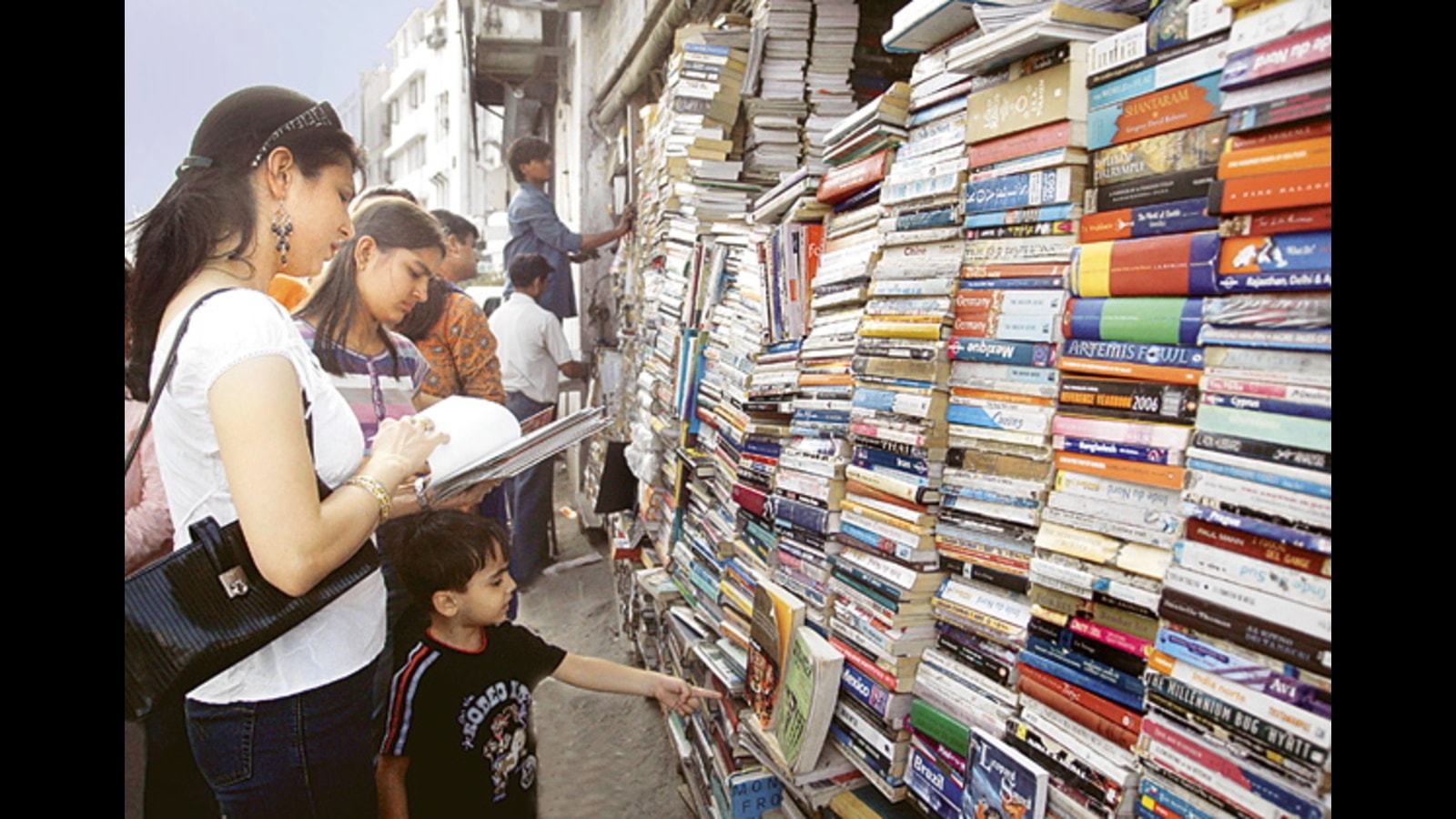

Equally passionate, Mansi Dhanraj Shetty (36), buys 15 books a month. “After moving to Mumbai and discovering second-hand books, I realized that there is no need to spend 1,000 rupees for two books when you can buy 10 for that amount. About half of my book purchases are used,” she says.

Used books aren’t always cheap. “Out-of-print copies or books unavailable in bookstores are expensive. Thrift stores carry quality books that you can’t find in regular bookstores,” says Shetty, who typically buys books she can read and then pass on. “But I’ve also bought some of the greatest thrift store keepers – obscure books on English and world literature, literary fiction, even a graphic novel in the history of the Parisian bookshop Shakespeare and Co. You don’t You won’t find them in any bookshop in town!’ she said.

These stores are also part of Shetty’s attempt to cultivate an eco-friendly reading habit, a need sparked after seeing heaps of old books dumped in landfills at Topsia in her hometown of Kolkata. “I had been building my personal library for years. Then, six years ago, it hit me, “Why can’t I give books to someone who wants them or get copies from someone who wants to unburden themselves?” She remembers thinking that such a practice would be “much better than dumping” and bought a domain name to create an online platform for it. Moving to Mumbai, she discovered SWAP Book, a book club that does just that – except its members only exchange books on a returnable basis. A huge community of used book readers, they also introduced Shetty to good sellers.

The used book trade in India is still largely unorganized, but online players including Amazon and some start-ups have entered the space. One of these actors is BookChor, created in 2015 by four students to meet the challenge of obtaining second-hand textbooks. Their pilot website aimed to meet the needs of their college students. In the first month, however, the site also received 5,000 visits and inquiries from students from other colleges. “There was also a demand for novels. Looking at the potential, we started looking at how to run a successful business and we haven’t looked back since,” says BookChor co-founder Alok Raj Sharma. In 2019, BookChor was selling nearly 5-10 books per year.

But the pandemic has changed things. “People used to be reluctant about e-books, but acceptance grew after printed copies became hard to access during lockdown. Today, commercial book buyers, people in positions of power who previously bought at airports, and even readers of fiction are turning to Kindle. Consequently, the used book market has been affected. Digital piracy and pirated copies sold as second-hand books are also hurting sales,” says Vikas Gupta, former president of the Publishers Association of India.

Gupta is right. During the initial lockdown, street vendor businesses like Hitler Nadar came to a halt. Even when things calmed down, the supply of books, usually purchased from raddiwalas and readers, was difficult as several buildings restricted access to vendors. Events have been canceled and have impacted BookChor’s business. While their inventory (10 lakh pounds) should have been useful, the restrictions around their warehouse in Haryana meant that it was inaccessible for a long time. Imports from the United States and the United Kingdom, which have a huge second-hand book market – BookChor’s other source – have also ceased.

They survived by offering great prices for group purchases online. Shetty, also the founder of Twice Told, has helped providers like Nadar harness the power of WhatsApp to reach readers.

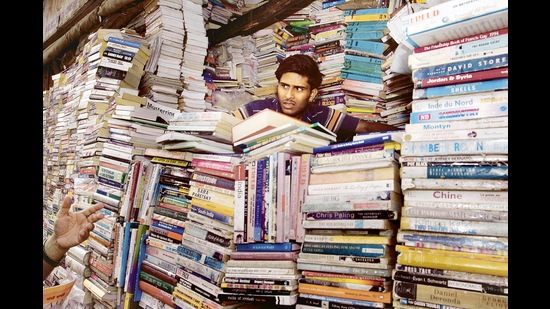

“I had no knowledge of WhatsApp. Mansi and Nitin from SWAP Books taught me,” says Nadar, whose group now has more than 250 customers. “I post 150 books on it every Sunday and people bid for the one. that they want. Instead of having only local customers, I now ship books all over India – to Assam, Haryana, Tamil Nadu and Gujarat. 60% of my sales now come from WhatsApp. The technology has been really beneficial,” he says.

While e-books have had an impact on sales of printed books, including second-hand ones, Alok Raj Sharma thinks doomsday predictions are overblown. Books are uploaded again, and BookChor’s first offline event received a fair response. “We expect pre-Covid numbers by the end of the year,” he says.

In fact, in Nadar’s experience, the pandemic made things better. “I have been in this business for 26 years. Over the past ten years, readership has been declining. It used to be that people asked for a good variety of books – on philosophy, literature, and some types of fiction. Then, after Amazon and Google, things got tougher. But reading has increased during the pandemic and now people are asking for old books and books on spirituality, among other things. »

Sharma thinks past predictions have never matched the actual numbers. “The 2014-2015 projections suggested that digital markets would take over physical books in two or three years, but that is not the case. There is no dedicated website for e-books, moreover, consumption is linked to internet penetration and India still has a fractured internet,” he says. “Affordability is also a factor. A Kindle costs approximately ₹8000, so when we talk about increased e-book sales, we think of a very privileged section. Since we are a middle-income country with a growing readership, I believe the sale of physical books will continue to grow and at a faster rate than e-books. It will take another 20 years before they take over in India.

The jury is still out on how soon e-books will take over, but demand for used books is a positive indicator for print books in general, especially since this market seems to be attracting readers who buy more than books, more regularly. And they are also insightful. When shopping over the phone, Nadar always informs customers of a book’s status while BookChor’s website has photos and a table showing status parameters.

But perhaps what holds regular used book buyers back is the idea that they, the reader, are part of stories told twice. Flowers, banknotes, postcards, train tickets, questionnaires are some of the collectibles that Aadil Desai has amassed over four decades of buying used books. “Sometimes if I find something interesting in a book at a used bookstore, I buy the book for it rather than the book itself,” he says.

Many sellers are also delighted. “Old books are fascinating. The printing, the paper, the smell of the pages, the black and white photos… There is beauty in all of this. It’s always fascinating to find what the previous reader left inside – letters, a 6 paise bus ticket, a Republic Day 1947 bookmark! Recently, I found a book on the Japanese war by Lara Bush,” says Nadar, who keeps an eye on these details and capitalizes on this fascination shared by his regular buyers.

“A lot of my books are second-hand,” says Amir Hasan (40). “They tell you two stories – one that’s in the book and one that’s about the previous owner(s).”

It’s these multiple stories – written and imagined – that continue to draw readers like Hasan and Desai to second-hand bookstores.

Pooja Bhula is a freelance journalist based in Mumbai. She is co-author of Intelligent Fanatics of India. She is @poojabhula on Twitter