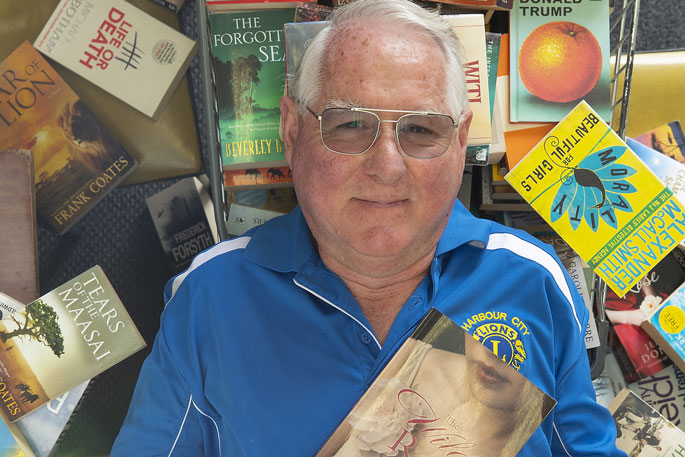

Donald Lawson is about to tear up the sailing record books

One rainy autumn morning in 2005, Donald Lawson received a phone call from his sailing hero, Bruce Schwab, asking if he would be willing to drop everything and join him on a trip to the East Coast.

Lawson, then 23, had honed his sailing skills for more than a decade, first at the Police Athletic League in Baltimore and Downtown Sailing Center, then on the Chesapeake Bay in prestigious regattas such as the Governor’s Cup. In these races, up to 20 boats compete over courses of up to 100 nautical miles. Lawson and his teammates had broken several speed records – and each time Lawson was one of the only black sailors.

At that time, there was no greater figure in American sailing than Schwab, who for the previous three years had been the only American to enter and complete two of the sport’s most hallowed single-handed sailing races. around the planet: the Around Alone and the Vendée. World. Lawson had bombarded Schwab with Myspace posts for months asking for advice on how to run better and faster. Schwab had been helpful, but this was the first time he had offered an invitation to sail his 60ft yacht, ocean planetthe boat he had used during his circumnavigations.

Lawson’s dreams had already stretched beyond those Chesapeake regattas – he wanted to sail around the world too, and he wanted to do it faster than anyone had ever done. But he needed practice. Immediately, he hopped on a bus from Baltimore to Portland, Maine, where Schwab was waiting for him. “It was an opportunity I knew I had a chance to take,” Lawson says. “It’s part of the mentality that you have to have, not coming from a rich family and being a black sailor – sometimes you only get one shot.”

The first night Schwab and Lawson were out on the water, a blizzard hit as they headed into a freezing headwind. Most skippers wouldn’t have left port in these conditions, but Schwab wanted to take advantage of the winds from the storm, which could propel them south. Schwab loved speed, and it was clear that his new apprentice did too. “The boat could sail perfectly on autopilot,” says Schwab. “But Donald was so delighted to be there that he refused to come down, preferring to sit outside and drive the boat for hours, against the wind, in the snow.”

Now 40, Lawson is an accomplished sailor on the verge of realizing his dream of circumnavigating the globe. In the fall, it will begin a decade-long effort to break dozens of world records, including an attempt to become the fastest person and the first black sailor to complete a solo, non-stop circumnavigation of the globe. This goal follows in the wake of Teddy Seymour and Bill Pinkney, the only other black Americans to sail alone around the world (they stopped along the way). Meanwhile, Lawson was chosen to lead the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Committee at US Sailing, the sport’s governing body. He also established the Dark Seas Projecta foundation that aims to bring people of color into sports.

Lawson grew up in Woodlawn, a predominantly black, middle-class neighborhood in Baltimore County. Her father was a Baptist preacher and an employee of the NASA Inspector General’s Office, and her mother was a computer technician and community counselor. In a family that prided itself on regimented goals – his younger brother and sister both joined the military – Lawson was an outlier with a lust for adventure. In 1990, when he was nine years old, his mother signed him up for the Police Athletic League and took him on his first field trip. Lady Maryland, a replica of a 19th century schooner that hosts field trips on the Chesapeake Bay. As the ship got under way, the Baltimore skyline dissolved over the stern. Ahead of us was the wide mouth of the Patapsco River and, beyond, the Chesapeake. Lawson found the captain and asked him how far he could take this boat. Around the world if you wanted, he said.

“It’s part of the mentality that you have to have, not coming from a rich family and being a black sailor – sometimes you only get one shot.”

Would it be so easy to escape? “When someone tells you there are people roaming the world and you can be one of them, it opens your mind to possibilities you never thought of before,” Lawson says. . But with all the white faces on the boats in the harbor that day, it was easy to think sailing had no place for a black Baltimore kid. At the time, he knew nothing of Seymour, who circumnavigated the world in February 1986 in honor of Black History Month, departing from Frederiksted, St. Croix, where an uprising in 1848 led to the abolition of slavery in Danish territory at the time. It would be another 17 years before he learned of Pinkney’s existence, who in 1992 became the first black sailor to complete a world tour via the southern capes. Sailing, Pinkney wrote, was “about escapism – escaping the bonds of conformity, racism and disrespect due to one’s origin”. The sea, he continued, “gave me the chance to prove my potential when placed on equal footing.”

In 1999, after graduating from high school, Lawson began working for the Downtown Sailing Center, where he became its first black instructor. Teaching novices to sail on different types of boats in the bustling waters of the Inner Harbor got Lawson up to speed quickly. Soon he was invited to join crews for races along the East Coast and in the Caribbean. It was then that he discovered the racist undercurrents in sport. “You start meeting people who don’t know you and they’re not totally comfortable with you,” he says.

After the trip with Schwab in 2005, Lawson started thinking about breaking speed records on his own terms, and doing it beyond the confines of a racing schedule. To pay the bills, he got his captain’s license at the Annapolis Seamanship School, which allowed him to deliver ships for boat owners in different locations. This work gave him access to a multitude of boats and an opportunity with each delivery to break personal speed records.

In 2009, Lawson began looking for sponsors who would allow him to acquire his own boat. This year it has finally arrived, in the form of a 60ft trimaran, one of the fastest sailing yachts in the world. Beginning in September, weather permitting, he will launch a campaign to break 35 solo world records over ten years, beginning with a California-Hawaii transpacific route record attempt; in January 2024, he will attempt a non-stop single-handed circumnavigation of the globe. For the class of sailing Lawson’s trip will fit into, the current world record is 74 days. Lawson will attempt to do so in 70.

“Sailing teaches a few things: good planning and prioritization skills, problem solving, self-reliance, resilience, high-level understanding of physics, math, hydro and aerodynamics” , says Rich Jepsen, vice president of US Sailing. “With tens of thousands of ocean miles under his belt, Donald has it all in abundance.”

In the meantime, Lawson helps break down the barriers ashore. After the 2020 murder of George Floyd, US Sailing formed a task force to educate community sailing groups across the country on the importance of cultivating sailors from all racial and economic backgrounds. Lawson was one of the first people Jepsen thought of for the initiative, along with Debora Abrams-Wright, Quemuel Arroyo, Lou Sandoval and Karen Harris. “I wish I could tell you that US Sailing, out of wisdom or generosity, started the task force on its own,” Jepsen says. But it was the volunteer leaders of community sailing organizations who pushed the national governing body to act.

Lawson hopes any black child who sets foot on a sailboat will have role models they recognize to show them the way. “I’m happy to say that probably in the next five or ten years you’ll see me more,” he says. “And who knows? Maybe they will be inspired to come and break my records.