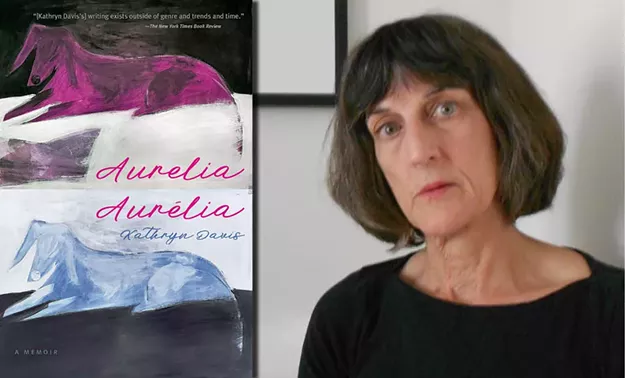

Book Review: “Aurelia, Aurelia”, Kathryn Davis | Books | Seven days

Readers of Kathryn Davis’s books have learned that, for her, the line between fiction and nonfiction is slippery.

There are passages in Davis’ richly imaginative novels that read like a first-person autobiography. And there are parts of her again Aurelia, Aureliaidentified on its cover as a memoir, which are ingenious fabrications, comprising two chapters, “Ghost Story One” and “Ghost Story Two”, which employ the wacky logic of dreams.

Davis is a maestro of atmosphere and mood, but she’s mischievous when it comes to delivering an orderly story. The plots of his novels are meandering, and his rendering of time is labyrinthine. What anchors the writing is its precision: an ability to find the words to summon into the reader’s mind the bizarre specifics of its characters and the minutiae of physical locations.

In Aurelia, Aureliashe applies these gifts to a very specific person – her husband, Eric Zencey, who died of cancer in 2019 – and the qualities of the places they knew and loved together, including Hubbard Park in Montpellier.

Davis, whose home is in Montpellier, is the author of eight novels, the most recent of which The Silk Road. She spends January through March each year at Washington University in St. Louis, where she is Hurst’s senior writer-in-residence. Among his honors are the Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize from the Susan B. Anthony Institute at the University of Rochester and the Morton Dauwen Zabel Prize and the Katherine Anne Porter Prize, both from the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Her late husband was also a writer, author of four books, including the superb historical thriller Panama and a collection of essays, Virgin forest: meditations on history, ecology and culture. The Gund Institute for Environment at the University of Vermont, where he was a fellow, created an award in his name, the Eric Zencey Prize in Ecological Economics.

The title of Davis’s new book illustrates his entanglement of the expository and the whimsical, the simple and the fantastic. Aurelia was the name of a ship that brought her to Europe for a student exchange; Aurelia is the name of a short story by 19th-century French writer Gérard de Nerval that Davis calls “romantic obsession driven to madness”.

Aurelia, Aurelia. There is a sort of transit that occurs between the place in your mind where memory resides, as firmly anchored as the house you grew up in, and the operative tool of thought, designed to transport you and your memory somewhere else, like across the ocean in a boat.

The narrative journey of these memoirs is peripatetic, mimicking how in our lives (and in our minds, in remembering) we wander among chance.

Davis moves forward and backward through the memories, elucidating an absence that has become another form of presence. She says she seeks “an abstraction…but up close, particular, a view of the particular self at a particular moment, necessary to the need of a host’s memory to carry it as far as possible out of the path of Memory”.

By “trail of memory” she surely means the pious versions that many of us succumb to when remembering. In contrast, Davis’ view of the past is harsh and accurate.

Writing about childhood, she describes herself as a girl mostly separated from the hustle and bustle around her – and always reading. His literary loves lasted: Edgar Allan Poe, Gustave Flaubert, Virginia Woolf, Samuel Beckett and, to a large extent, the bizarre tales of the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen.

Also stirred in the bouillabaisse of the associations of this memoir are the wrecks and wrecks of an era: that of Ingmar Bergman The seventh sealmusical comedy Brigadoonillustrated Golden Books, James Bond and Dr. No’s metal hands, “Mark Trail” comic, Barbie dolls, Jell-O, Vicks VapoRub and Lipton’s Noodle Soup.

Davis does not chronologically sequence her childhood scenes, her reading and writing life, her love affairs, or her husband’s terrible illness. The end of his life does not come at the end of the book but in the middle:

It is different from washing the body after the person dies. Pass a wet washcloth over the forehead, forehead, eyelids — still eyeballs. The desire to do no harm is still there, heightened by the lack of response to anything resembling desire. The pale blue washcloth swimming in the pot of warm soapy water. If emancipation has occurred, the body will not feel. The body will shine.

Is it an expression of shock and grief? Not in the usual way. But countering the elevation of this passage into metaphysics is an extremely tactile depiction of the preparation of a body: the sobriety of a grieving person doing what is necessary before the corpse goes to the oven of a crematorium. .

Through the detours and dead ends of Davis’ prose, readers can follow the narrator’s search to confirm that what she believes she remembers was actually real, always echoing with meaning. Sometimes she seems eager to be haunted, and she wonders if Lucy, the family dog she and Eric walked together in Hubbard Park, might still see it:

That flash of something invisible out of the corner of your eye – it didn’t need to show up to let you know that where you are isn’t just any place you’ve been before, the surface of the world is a mess like from the beginning, tree roots and stones underfoot — until, suddenly, a ray of sunshine! melting ice dripping from an overhanging tree onto a dead tree, and before him a dark shape like a stone perched on a picnic table, slightly arched and unrecognizable, Lucy on the ground at his feet.

It’s not grief as a primal cry, but elegy with a strangely light touch. The effect might even be called comic in the Shakespearean way of wrapping pain in enchantment. Memory opens and reopens and constantly leads back to the fact of the death of a loved one; the result, however, is not just loss but transformation. As in the fairy tales Davis loved as a child, which gave him “that thrill of ecstasy which is an unmistakable symptom of the creative act”:

Your tenure on this earth, where you could choose to remain (despite its perils, the evil cause-and-effect machinery embodied by snuffbox goblins and gumdrop poodles), would be infinite, but once dead, you would have no no choice but to leave forever and ever. You just had to imagine a door, the door you couldn’t go through, and the next thing you knew the door would open and behind it would be…another door! And another!

Beyond death, Eric continues to appear in the story – for example, in a description of him helping plan his own memorial gathering. In the scenes remembered before and after, he was and is at the same time.

Although the sequence of this memoir is messy – some might say disturbed – a careful reader will find many catches such as recurring words, developing questions. The brevity of the book keeps all parties in mind.

Indeed, this book is all about transitions, never arriving or settling comfortably into place. Recalling a pianist friend playing Ludwig van Beethoven’s Bagatelles, Op. 126, “the last piano music he wrote before his death”, Davis considers how this music juxtaposes “the sublime and the ancient”.

At first glance, the contrasts are so wild that one would think the overall effect would be incongruous, even chaotic, and yet – as Lois plays it for me – the music seems to inhabit both realms equally, almost as if simultaneously, sweetness made sweeter by its leap into disharmony, disharmony more discordant by its embrace of sweetness.

Cleverly defending his own juxtapositions of soft and abrupt, continuous and disjunctive, Davis writes: “A transition – the moment of transition – when performed as perfectly as Beethoven did in his trifles and the later quartets , is capable of accomplishing this sleight of hand, the moment-in-between, the phantom-moment, inhabited by both parties.”

Extract Aurelia, Aurelia

When it comes to living with a dying person, it’s hard to tell the difference between the unnecessary and the impossible. Tedious as the requests are – organize a compartmentalized pill tray around a week of thirty-four different types of pills totaling 420 pills in total, separated by time of day (morning, noon, evening, bedtime ), not to mention the follow-up for example, this least favorite but crucial Nero Wolfe paperback (Trinity Homicide) that had to be physically applied to the upper chest in a totemic way, like a mustard bandage, to ward off the shocking pain of shingles – that path was the one I clung to. ” Get up ! Get up, Eric! I should have said that. I told myself that what I was following was the path of good, but I knew that good was not going to do a little good.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/gray/LMS4GGRVH5AB5IAHCD22D6S3SA.jpg)